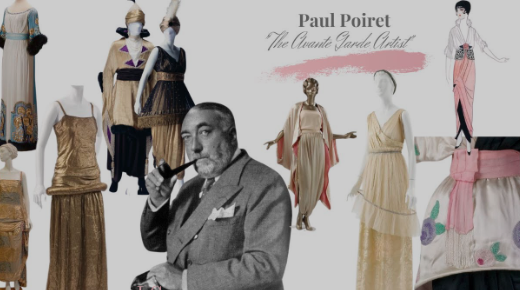

Paul Poiret (20 April 1879 – 30 April 1944, Paris, France) was a French fashion designer, a master couturier during the first two decades of the 20th century. He was the founder of his namesake haute couture house. Early life and career.

Poiret was born on 20 April 1879 to a cloth merchant in the poor neighborhood of Les Halles, Paris. His older sister, Jeanne, would later become a jewelry designer. Poiret’s parents, in an effort to rid him of his natural pride, apprenticed him to an umbrella maker. There, he collected scraps of silk left over from the cutting of umbrella patterns, and fashioned clothes for a doll that one of his sisters had given him.While a teenager, Poiret took his sketches to Louise Chéruit, a prominent dressmaker, who purchased a dozen from him. Poiret continued to sell his drawings to major Parisian couture houses, until he was hired by Jacques Doucet in 1898. His first design, a red cloth cape, sold 400 copies. He became famous after designing a black mantle of tulle over a black taffeta, painted by the famous fan painter Billotey. The actress Réjane used it in a play called Zaza, the stage then becoming a typical strategy of Poiret’s marketing practices.

In 1901, Poiret moved to the House of Worth, where he was responsible for designing simple, practical dresses,called “fried potatoes” by Gaston Worth because they were considered side dishes to Worth’s main course of “truffles”.The “brazen modernity of his designs,” however, proved too much for Worth’s conservative clientele. When Poiret presented the Russian Princess Bariatinsky with a Confucius coat with an innovative kimono-like cut, for instance, she exclaimed, “What a horror! When there are low fellows who run after our sledges and annoy us, we have their heads cut off, and we put them in sacks just like that.” This reaction prompted Poiret to fund his own maison. Career expansion …..Poiret established his own house in 1903. In his first years as an independent couturier, he broke with established conventions of dressmaking and subverted other ones. In 1903, he dismissed the petticoat, and later, in 1906, he did the same with the corset.Poiret made his name with his controversial kimono coat and similar, loose-fitting designs created specifically for an uncorseted, slim figure. Poiret designed flamboyant window displays and threw sensational parties to draw attention to his work. His instinct for marketing and branding was unmatched by any other Parisian designer, although the pioneering fashion shows of the British-based Lucile (Lady Duff Gordon) had already attracted tremendous publicity. In 1909, he was so famous, Margot Asquith, wife of British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, invited him to show his designs at 10 Downing Street. The cheapest garment at the exhibition was 30 guineas, double the annual salary of a scullery maid.

Poiret’s house expanded to encompass interior decoration and fragrance. In 1911, he introduced “Parfums de Rosine,” named after his daughter, becoming the first French couturier to launch a signature fragrance, although again the London designer Lucile had preceded him with a range of in-house perfumes as early as 1907. In 1911 Poiret unveiled “Parfums de Rosine” with a flamboyant soiree held at his palatial home, attended by the cream of Parisian society and the artistic world. Poiret fancifully christened the event “la mille et deuxième nuit” (The Thousand and Second Night), inspired by the fantasy of a sultan’s harem. His gardens were illuminated by lanterns, set with tents, and live, tropical birds. Madame Poiret herself luxuriated in a golden cage. Poiret was the reigning sultan, gifting each guest with a bottle of his new fragrance creation, appropriately named to befit the occasion, “Nuit Persane.” His marketing strategy, played out as entertainment, became the talk of Paris. A second scent debuted in 1912 – “Le Minaret,” again emphasizing the harem theme.

.In 1911, publisher Lucien Vogel dared photographer Edward Steichen to promote fashion as a fine art in his work.[10] Steichen responded by snapping photos of gowns designed by Poiret, hauntingly backlit and shot at inventive angles.These were published in the April 1911 issue of the magazine Art et Décoration.

According to historian Jesse Alexander, the occasion is “now considered to be the first ever modern fashion photography shoot,” in which garments were imaged as much for their artistic quality as their formal appearance. A year later, Vogel began his renowned fashion journal La Gazette du Bon Ton, which showcased Poiret’s designs, drawn by top illustrators, along with six other leading Paris designers – Louise Chéruit, Georges Doeuillet, Jacques Doucet, Jeanne Paquin, Redfern, and the House of Worth. However, notable couture names were missing from this brilliant assemblage, including such major tastemakers as Lucile, Jeanne Lanvin and the Callot Soeurs. ….In 1911, Poiret launched the Les Parfums de Rosine, a home perfume division, named for his first daughter. Henri Alméras was employed as a perfumer by Paul Poiret as of 1923, though certain sources suggest he had worked there since 1914. ……Also in 1911, Poiret launched the Les École Martine, a home decor division of his design house, named for his second daughter. The establishment provided artistically inclined, working-class girls with trade skills and income

In 1911 Poiret leased part of the property at 109 Rue du Faubourg Saint Honoré to his friend Henri Barbazanges, who opened the Galerie Barbazanges to exhibit contemporary art. The building was beside Poiret’s 18th century mansion at 26 Avenue d’Antin.Poiret reserved the right to hold two exhibitions each year. One of these was L’Art Moderne en France from 16 to 31 July 1916, organized by André Salmon. Salmon called the exhibition the “Salon d’Antin”. Artists included Pablo Picasso, who showed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon for the first time,Amedeo Modigliani . Poiret also arranged concerts of new music at the gallery, often in combination with exhibitions of new art. Collapse of the Poiret fashion house.

Early in, Poiret left his fashion house to serve the military. When he returned in 1919, the business was on the brink of bankruptcy. New designers like Chanel were producing simple, sleek clothes that relied on excellent workmanship. In comparison, Poiret’s elaborate designs seemed dowdy and poorly manufactured. (Though Poiret’s designs were groundbreaking, his construction was not – he aimed only for his dresses to “read beautifully from afar.”) In 1922, he was invited to New York to design costumes and dresses for Broadway stars. He took his top designer (France Martano) and an entourage with him, enjoying the elegant life at sea (see photos). New York City, however, was not home and he soon returned to Paris leaving his top designer there in his stead. Back in Paris, Poiret was increasingly unpopular, in debt, and lacking support from his business partners. He soon left the fashion empire he had established. In 1929, the house was closed, its leftover stock sold by the kilogram as rags. When Poiret died in 1944, his genius had been forgotten. His road to poverty led him to odd jobs, including work as a street painter, selling drawings to customers of Paris cafes. At one time, the ‘Chambre syndicale de la Haute Couture’ discussed providing a monthly allowance to aid Poiret, an idea rejected by Worth, at that time president of the group. Only his friend and one of his right hand-designers from his pre-WWI era, France Martano (married name: Benureau), helped him in his era of poverty, when most of Parisian society had forgotten him. At the end of his life, he dined regularly in her family’s Paris apartment and she ensured he was not wanting for food. (He’d previously erased her from his memoirs as, after designating her as his long-term replacement to design for Broadway in 1922, he was infuriated that she became an independent couturier upon her return to Paris.) His friend prevented his name from encountering complete oblivion, and it was Schiaparelli who paid for his burial.